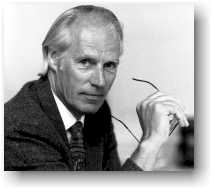

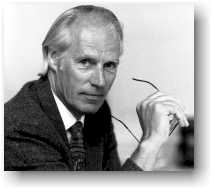

INSIGHTS: Sir George Martin

Celebrating 45 years in the music business

Interviewed by Mel Lambert in 1994  Recognized throughout the world of music as one of our most versatile and innovative producers, conductors and arrangers, Sir George Martin is beginning to wind down after a career that spans almost four and a half decades. Entering the industry in 1950 after studying music at the famous Guildhall School of Music, London, and playing oboe professionally, George began recording classical music. He was made head of the EMI's Parlophone label in 1955, and during the next 15 years worked as producer with a wide cross section of artists, culminating in his eight-year association with The Beatles. Recognized throughout the world of music as one of our most versatile and innovative producers, conductors and arrangers, Sir George Martin is beginning to wind down after a career that spans almost four and a half decades. Entering the industry in 1950 after studying music at the famous Guildhall School of Music, London, and playing oboe professionally, George began recording classical music. He was made head of the EMI's Parlophone label in 1955, and during the next 15 years worked as producer with a wide cross section of artists, culminating in his eight-year association with The Beatles.

In the mid-Sixties he formed a production company with three other producers, and in 1970 opened Air Studio in London's Oxford Street; followed nine years later by Air Montserrat, which in 1989 was destroyed by a hurricane. In 1993 Air Studios relocated to its new home at Lyndhurst Hall in North London. During the Seventies, George worked extensively with American artists here in the States, including The Mahavishnu Orchestra, America, Jimmy Webb, Neil Sedaka and Cheap Trick. He also worked with Paul McCartney on two solo albums, "Tug of War" and "Pipes of Peace."

He has composed music for "A Hard Day's Night" (for which he received an Oscar nomination), "The Family Way," "Yellow Submarine," "Live and Let Die" (for which he won a Grammy® Award), and "Give My Regards to Broad Street," with Paul McCartney. He was also commissioned to compose a suite for harmonica and strings for celebrated harmonica player Tommy Reilly and the Orchestra of the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields.

Recipient of an honorary doctorate of music from the Berklee College of Music, in 1987 George produced and directed a new recording of Dylan Thomas' "Under Milk Wood," followed by an album with Jose Carreras of Andrew Lloyd Weber songs. In July 1992 he was invited to perform at the Festival D'ete of Quebec, with the Quebec City Symphony Orchestra and The King's Singers. In December of that year, he produced a special live version of "Under Milk Wood" at Air Lyndhurst in aid of The Prince's Trust.

Although Sir George has reduced his work load during recent years, in mid-1993 he produced a cast recording in New York of The Who's "Tommy," followed in October with symphony concerts in Sweden and Brazil. Recently, he completed "The Glory of Gershwin" with Larry Alder, assisted by Elton John, Sting, Carly Simon, Sinead O'Connor, Elvis Costello, Cher, Peter Gabriel and a host of other stars. "Gershwin" managed to reach #2 in the English charts, and went Gold within 10 days of its release. "Mix" caught up with this prolific producer by telephone to his home base in West England.

How do you define your role as a Producer in the studio?

In 1950, when I started working in the business, the record industry was a pretty small affair and the amount of record producers was also pretty small. The word "record producer" was never used; the role was something that evolved. If you ask me to define the role of a producer, I'd have to define the way in which I regarded myself over the years. Producers come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. There is a tendency these days for producers to come up from the engineering ranks; some very good producers have emerged from that kind of background.

You have more of a background as a musician and arranger. What do you bring to a production with that kind of experience?

A good producer has got to really have an understanding of music, and a catholic love for it. Unless you're very specialized, I think that you have to have a very universal approach to music; to have the temperament to like a lot of music. Which, fortunately or unfortunately, I do! If you're very narrow in your outlook, you're not going to make a good record producer, because you have to be pretty tolerant too. But, in terms of music, it is very important to have an understanding of how music works, although I don't think it's absolutely a prerequisite that you have a musical education. I think that if you've got to have a feeling for music, it does impinge very heavily on the resulting production.

A record producer is responsible for the sound "shape" of what comes out [of the session]. In many ways, he's a designer - not in the sense of creating the actual work itself, but he stages the show and presents it to the world. People say "Yes, that was a marvelous show that Leonard Bernstein did." But it wasn't Leonard Bernstein who staged it; it was somebody else. The record producer is the guy who actually puts the frame around everything, presents it to the public, and says "This is what it is." It's his taste that makes it what it is - good or bad.

Do you choose the material? Having got to know an artist, a group or an orchestra over a period of time, do you have a better understanding of their musical directions?

Yes, indeed I do. One of the fundamental aspects in terms of pop records is the song or the material; the actual creative work you're dealing with. If you're dealing with something that's got really good, raw material, then you're task is made that much more easy. If you're dealing with dross then, no matter what a genius you are as a producer, it's still going to be rubbish. The critical factor is the beginning; the song, the music you're dealing with.

How do you determine if a song is good or, to use your words, dross? Suppose you turn up at a session and there are maybe 10 songs the band is considering recording. Some of them you like and some of them you may not like. What's the criteria you use to decide that the latter go in the "dross" pile?

That's a good question. I think, again, it's taste. Obviously if you look at any amount of songs or records, everyone can have a different opinion. When I did this album recently of Gershwin ["The Glory of Gershwin," celebrating Larry Adler's 80th birthday; recorded in November 1993] we had 18 songs [recorded by] 17 artists. The critics actually were completely at loggerheads with each other. One said the Peter Gabriel track was stunning; another didn't rate it at all; another guy said the Jon Bonjovi track was the worst thing he'd heard in years; another one said it's the best track on the album! So it's "horses for courses." The taste of the producer does affect what material is selected. But I think that he's got certain yardsticks to go by. It is possible to categorize what is a good song, and what's a bad song. There are bad songs that have made it but, generally speaking, the material that does makes it is better than the stuff that doesn't.

So you tend to rely on things like the "tingle factor?" Some intuition that says this is a damn good song. I like it. I think the people that we're inviting to listen to this music will like it. So, on that basis, it's probably worth recording?

Yes. I think the writer is not the person who is likely to be able to judge that best of all. It does require another person who can look at it dispassionately, because everyone likes their own baby better than the baby next door! It is inevitable that a writer will think more highly of his work than somebody else. And they get blind to the fact, and they get jealous too. If you don't like a thing that they've worked on and refined, and thought it was pretty good, they get very upset about it. So you have to be very careful.

| George Martin with The Beatles

in Abbey Road Studio #2 |

Did you find that was the case with what the world would probably consider as your most famous clients, The Beatles? John and Paul wrote a great deal of material, but occasionally you weren't that keen on a particular song. Maybe the lyrics didn't work for you?

I was very lucky with the Beatles, because almost every time they came to me with something it was brilliant. In the beginning, some of the early material from the "Love Me Do" days was the best I could dig out of them, and I wasn't very happy about it. I didn't think it would be a hit, and I needed to find "hits" for them. The kind of material they had been writing wasn't, in my opinion, likely to set them alight. But once we got "Please, Please Me" under our belt, they seemed to realize what a good song needed to be. From that moment on, through "I Wanna Hold Your Hand" and "She Loves You," they came forward with the most wonderful material. It was brilliant; it was different. Every one took a new twist, and that pretty well maintained the whole of their career. Occasionally towards the end they would get a little bit lazy. There were some things during "The Magical Mystery Tour" - the freaking out bits - that didn't seem to make much sense.

In the main, however, the material The Beatles gave to me was gold; there was practically no dross at all. I've worked with other people who've brought me something and I've said "I think you ought to go back and re-write that." Or that we ought to scrap it completely. Or maybe put a different kind of tune in the middle, and alter it. I think that's the creative part that a producer can do, he can shape the music. If the producer is able to convince the artist that he knows what he's talking about, he can actually lead the writer into producing better work than maybe the writer does by himself.

The songs that Paul and John wrote together were really wonderful material. There's no question in my mind: they are the greatest songwriters of this century. (I don't think I'm being biased, although I happened to work with them all that time!) It doesn't mean to say that everything they wrote was marvelous, but it was the highest consistency of success that I've ever experienced.

In the Seventies, you started to work more with American bands in L.A. and other cities.

I did that because they asked me to, and it was a way of earning money. Also, it was a great relief after nearly a decade of working with The Beatles to have the freedom to work with other talent. If someone came up to me and said "Would you make an album with me?" I could say "Why not, let's give it a whirl. If it doesn't work out, no problems." But you didn't have the awesome responsibility of saying "God, I've got to worry not just about this single and album, but next year, the year after that and.." It was a kind of relief when it all ended and I was able then to go off and have one-off projects with different people.

Was it a passive role; they came to you? Or did you search out people that you'd always wanted to work with, and let it be known that, if the opportunity presented itself, you wouldn't mind working with them in the studio?

There were lots of people I would have liked to work with, but life is too short. Nowadays I'm turning things down because time is very precious. To make an album you've got to devote almost half a year of your time; it's important now that I do not to fritter my life away.

Who of the people you haven't worked with would you like still to have the opportunity to record?

There are an awful lot. A lot of people I admire enormously. I think Elton John is terrific; he's one of the people I would love to have made records with. I think enormously highly of Sting. Bob Dylan - I had the pleasure of working with him in Japan recently. He's one of the most interesting writers we've had in my lifetime.

When you began to work increasingly in America, did you notice a different kind of American-style production, versus a European or English style?

No, I don't think so. Music is a universal language. Back in the Seventies, while working with American musicians, there was a slight difference - maybe the horn sections are a little bit more crisp. Rhythm sections had a particular sound, a kind of L.A. sound - a mixture of synths, keyboards and guitars that was quite distinctive. I didn't want to get into the trap of having that kind of sound; I like to have rhythm sections the way I always felt them to be. I really think the records I made would have been the same had I been making them in America or in England.

What do you look for in a studio? A good engineer? Good technical performance?

These days, people tend to forget that sound begins in a room - the physical environment makes all the difference. What the studio itself is going to sound like? What microphone techniques are going to capture those sounds? If you have a good sound in a studio, and an engineer who knows how to use microphones, that's half the battle. Today people seem to forget the first part, and seem to get straight into the manipulation [at the console]. I think that a knowledge of acoustics - the way music should sound in a room - is very important.

Of course, after that, you have the best equipment - very good microphones, a really good desk and good monitoring. A lot of control rooms I've worked in might have had good monitors, but they haven't paid enough attention to the acoustics in the room itself. You would end up with varying characteristics that were quite markedly different wherever you stood. I like something that I know is consistent. The engineer has got to be somebody who has a good sense of sound, and understands what you're trying to get. Again I've been lucky in working with people who are very fine engineers and musicians themselves. If I work with them long enough we tend to know each other so well that we don't have to say a great deal to each other; they tend to know what you're looking for.

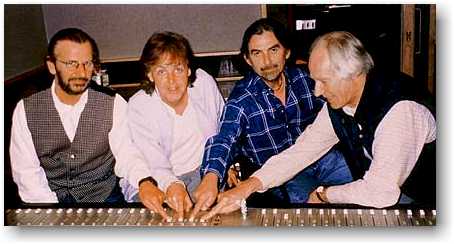

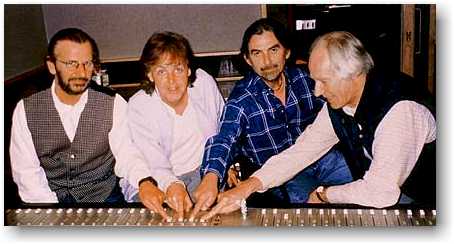

| George Martin with the surviving members of

The Beatles during production of "Anthology." |

You don't consider yourself to be a very technical producer. Do you tend to get the sound you want in the room, and then leave it pretty much up to the engineer to give that back to you in the control room?

It depends if we're talking about a rock and roll session with guitars and keyboards, drums - obviously you have a particular way you'd like the group to sound. You might say that drum sounds a bit dull or like it to be "snappier" - those little subtleties of difference of taste that every producer has.

When it comes to other sounds, like horns and orchestral session, then I will be very particular about the kind of sound I want. Again, it's something that I believe has to start in the studio. If you're dealing with an orchestral sound you've got to have a good room. You get it right there, and then you go and check in the control room.

The engineer has to realize the kind of sound you're looking for, in [terms] of clarity and good "liquid" sound from the strings, and so on.

Do you try and keep it simple? Do you believe in "Less is More" as a philosophy?

Less is More? Yes, absolutely! Certainly, whenever I considered putting an arrangement together for a song, whether it's purely working with the artist and the group and backing vocals, or a full- blown orchestra that I'm actually scoring, then I think that "Less is More" is a very good principle. It's fairly easy to learn the rules of orchestration and write for instruments. The difficult bit is knowing where to stop, and knowing what to leave out. Because every bar and every note that you come to is a little fork in the road; you can go one way or the other. You are continually making decisions. I say to myself "Pull back there. Don't do that. That's over the top. Let's come back here; let's make it simpler, cleaner lines."

In other words, I try and make an arrangement something that you can hear distinctly but beautifully. Don't clutter; make sure that whatever you add doesn't get in the way of things. If you're going to make an effect, make sure it's a good one. It is summed up very much with minimalism. Of course, I've been guilty as anybody of lush orchestrations. But I've tried to be fairly clean in my writing.

Continuing the studio theme, Air Studios, London - of which you enjoyed part ownership - was completed in the early Seventies. Was the idea behind Air London and Air Montserrat that you needed a more controlled environment; one that you could become more familiar with on an ongoing basis?

Yes. Every studio has good things and bad things about it. So you think to yourself, "If I had a studio that I've designed and built myself, then it's bound to be exactly what I want." Certainly, when we built the first Air Studio that was true; I was very pleased with the sound of Air Studio #1 in Oxford Circus. It became a very popular room. The people we had working there developed a particular style of working which I was very pleased with.

Montserrat Studios began, purely and simply, because I'd been doing so much work in America. I've worked in many, many studios and, although they were all pretty good, they lacked what I was looking for. I thought maybe I could have a studio near America that I can persuade people to come to, and which fits my bill. That's why I built Montserrat. [Opened in 1979, the studio complex was subsequently destroyed by Hurricane Hugo, which devastated the remote Caribbean island in 1989 - ML.]

The latest project is Lyndhurst Hall, our new studios in Hampstead [North London], where we've got the biggest and the most expensive and the most complicated - but also the most beautiful studio I've ever had. It's certainly my last one; I won't do any more after this! There are lots of other studios I've worked in I still enjoy, but I like my own one best of all.

Was the design of the largest studio at Air - The Hall - reflective of your move towards orchestral productions? A studio where you could record soundtracks, and more complex choral productions?

Yes, I've come full circle. When I started in 1950, the first thing I did was record classical music, and nothing else. Curiously enough, some of those orchestral recordings I made in the early Fifties have recently been re-issued by EMI, which is very flattering. They came to me and asked me: "Did you produce these?" And I said, "Yes, I did" "Well," they said, "we're going to re-issue them. Can we put your name on them?" To which I said: "Of course." Yet I reflected a moment. "Of course you didn't ask me in the Fifties; I never got my name on them in those days." But it's very nice to have that kind of reflection.

I do like live music. Having spent all my life making recordings, it may seem funny but I really enjoy working with musicians, and getting something out of them. Funnily enough, this Gershwin album ["The Glory of Gershwin"] was recorded almost completely live. Elton John, Sting, Elvis Costello and so on, were recorded with the orchestra in The Hall at Air Lyndhurst. It was good fun - almost like doing a concert! Cher came in and she saw the orchestra, and said "Are they going to be there when I'm singing?" "Yes," I said. "Oh, I've never done that." "Well," I said, "it's quite fun, because it means that if you don't like what they do, we can change it. If the key doesn't suit you, we can change it around. Or if you don't like a phrase, we can modify that too." She found it an interesting and enjoyable experience, even though she'd never done it like that before.

|The majority of the Gershwin sessions were recorded at the Hall?

Yes, almost everything. The Carly Simon basic tracks was done in New York, but I put the orchestra on in the Hall. The only orchestral sounds that weren't done in Air Studios, ironically, was "Rhapsody in Blue," which I did with Larry [Alder] at the very end. We were running out of time to finish the record, Air was booked solid and I couldn't get in. I was very cross that I couldn't record him in Air, but we booked into Abbey Road #1.

Let's turn to other recent sessions. A cast recording for the New York production of "Tommy," released in July 1993. What brief did you received from Pete Townsend?

Pete rang me up and said "We've got a show coming up of 'Tommy.' It's been running in La Jolla [California, during a provincial tour] and we'll need a cast recording. Would you like to do it?" So I said, "Pete, thank you very much for asking me, but why don't you do it yourself?" "First of all," he said, "I'm really too close to it to give it a good judgment; secondly the show's going out [on tour] and I don't want to worry about the recording. Anyway, you can do it better than I will." Which was very sweet of him.

It's an incredible show. I went to see "Tommy" many times and got to know it pretty well before we went into the studio. I had to decide just how I was going to do it - it had to be done very quickly. Obviously, when you've got a show that goes on every night, the cast are bound to get a bit tired. So we had to work very fast to get the best out of them. But it worked very well - well enough to get a Grammy Award [for Best Cast Album].

Where did you record the "Tommy" cast album?

New York. We had to do it there, because I wanted the cast and the stage band. We recorded on a Saturday and Sunday. I went to New York and looked around all the studios. In the end I chose the new Hit Factory; it's got a nice big room with some [isolation] booths. It worked out very well indeed. We mixed the tracks back in England.

You also remixed the soundtrack album for "Backdraft." Do you enjoy film work?

Hans Zimmer is an old friend of mine; we used to work together back in the early days in England. While he was scoring "Backdraft," Hans rang me up and said that he was working pretty much round the clock, and the film company was pushing this film out earlier than they had said. "They want me to finish the score sooner than they said originally, and they also want to have a soundtrack record out almost straight away. It would be a tremendous help to me if you came in and did [the soundtrack] for me, so that I can concentrate on the writing side." That's what we did. I came in to L.A., and we worked side by side on that project. I mixed the soundtrack album while he was still recording the film track. He's such a good musician and a hell of a nice guy anyway, it was a delight.

A lot of your recent projects have been with live music. Obviously the Hall at Lyndhurst lets you record some of these sessions, but you've been in Rio and Sweden for classical performances. Do you like to conduct a large orchestra, and bring the score too life?

Yes, it's inevitable human nature. It's a great buzz to go out there and be applauded. I've got quite a collection of orchestral symphonic scores that I've built up over the years, so from time to time I do concerts. I do them in England, but also abroad. In Scandinavia they keep asking me to go back, and I did a concert in Brazil last October. I've got concerts lined up for next year in Spain and Argentina. I don't want to make a career out of it, but it's nice to perform something and have lots of people clapping and saying you're good, even if you know you're not!

Do you find time to write? Do you still have a musical bent in that direction?

Yes, I do. I've been doing music for plays and that kind of thing. I did all the music for "Under Milk Wood." [A spoken-word recording of Dylan Thomas' novel, with Anthony Hopkins, Jonathan Pryce and Freddie Jones, with Welsh actors and singer in supporting roles, including Sian Phillips, Bonnie Tyler, Tom Jones and Harry Secombe.] I still keep my hand in a little bit, but I'm tending to wind down now.

Were you tempted during the recording of "Under Milk Wood" to have another producer work with you? Having written the score and arrangements, and then conducting the orchestra and choir, you also produced the album. Was it easy to handle all of those roles simultaneously?

Yes, I enjoyed it. I guess that you have realized that in my life I like to do lots of different things. "Under Milk Wood" was nice, because I was working with Anthony Hopkins, and he was directing the actors. We also did a live performance [in December 1992] of "Under Milk Wood" at Air Lyndhurst, which Prince Charles came to [as president of The Prince's Trust].

Tony [Hopkins] did the direction for that project, and helped put together the live show. I like working with actors, putting together a sound picture - using sound effects as well as music in the background.

We spoke earlier about three artists that you'd like to have worked with. Were there any productions that you've enjoyed through the years, but which could have been better?

I don't think I can honestly give you any example of that because it's not the way I think. If I hear things on a record that I don't like, I say "Well, okay, that's it." And I tend to write it off. All the records that I consider to be great, I like unqualifiedly. It would be very arrogant to say if I'd done that it would be much better. Some of the early Beach Boys records are still to me absolute bloody magic; I couldn't fault them and I wouldn't want to change them.

Any sessions you'd rather have avoided?

Yes. Obviously you don't record all your life without having some real boo-boos. I once had a flirtation with heavy metal, and I regretted it very much. It didn't seem to me to have any sense. It would be wrong to quote artists to you, but there have been a very small amount of people that I would rather not have worked with. But you don't really know until you actually start working with someone just how it's going to work out. And, if you're adventurous, you must try different things - and I've certainly tried lots of different things.

The vast majority of everything I've done has been enormously enjoyable, and successful too! But I think that's the essence of my approach to records. If it's not going to be enjoyable, don't do it, because life is too short. I've always tried to look ahead whenever I've flirted with an artist. Shall I make that record? Will I get on well with them? Will it be a good relationship? That's the most important thing of all. Unless you have that good relationship, I don't think you make good music!

©2026 Media&Marketing. All Rights Reserved. Last revised: 01.20.09 |

Recognized throughout the world of music as one of our most versatile and innovative producers, conductors and arrangers, Sir George Martin is beginning to wind down after a career that spans almost four and a half decades. Entering the industry in 1950 after studying music at the famous Guildhall School of Music, London, and playing oboe professionally, George began recording classical music. He was made head of the EMI's Parlophone label in 1955, and during the next 15 years worked as producer with a wide cross section of artists, culminating in his eight-year association with The Beatles.

Recognized throughout the world of music as one of our most versatile and innovative producers, conductors and arrangers, Sir George Martin is beginning to wind down after a career that spans almost four and a half decades. Entering the industry in 1950 after studying music at the famous Guildhall School of Music, London, and playing oboe professionally, George began recording classical music. He was made head of the EMI's Parlophone label in 1955, and during the next 15 years worked as producer with a wide cross section of artists, culminating in his eight-year association with The Beatles.